How low did they go? USEPA Issues Proposed MCL for PFAS in Drinking Water

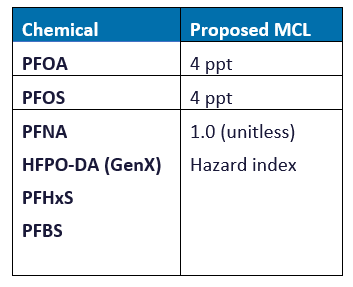

Yesterday, on March 14, 2023, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced a proposed National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR) including Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) for six per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) chemicals in drinking water. This includes perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA, commonly known as GenX Chemicals), perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), and perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS):

ppt = parts per trillion or nanograms per liter (ng/L)

ppt = parts per trillion or nanograms per liter (ng/L)

The proposed rule would require public drinking water systems to monitor for these PFAS, notify the public of the levels of these PFAS, and reduce exposure if they exceed the proposed standards.

Although some states have developed their own PFAS MCLs, many abstained or issued non-regulatory guidance values. After the MCL is finalized (targeted at the end of 2023), public water systems have a three-year window to comply. The stricter between state MCLs and the final federal MCL will apply—which on the surface makes sense, but practically gets sticky, as there are states that have released MCLs for a different suite of PFAS compounds.

For example, Massachusetts has an MCL set at 20 ppt for the sum of PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA), and perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA). PFHpA and PFDA in the Massachusetts MCL are not included in the EPA’s MCL, and the Massachusetts MCL does not include GenX or PFBS, which are included in EPA’s MCL.

Technical Background

In 2022, the EPA issued interim updated Lifetime Health Advisories (HAs) for PFOS and PFOA, and final HAs for HFPO-DA (GenX) and PFBS. The lowest HA was for PFOA at 0.004 ppt (equivalent to 4 parts per quadrillion). The basis for that value was decreased serum antibody concentration in children observed in human epidemiological studies. The current proposed MCL of 4 ppt for PFOA is 1,000 times greater than the HA. MCLs are based on both health effects, technical feasibility, and economic feasibility. The EPA selected 4 ppt as an MCL because it is a level that can be reliably measured.

The proposed MCL evaluates PFNA, HFPO-DA (GenX), PFHxS, and PFBS together as a mixture. A hazard index (HI) is a tool used to evaluate non-cancer health risks of mixtures. A HI of less than or equal to 1.0 indicates that non-cancer adverse effects are not likely to occur. Non-cancer endpoints are more sensitive than cancer outcomes for PFAS, so the HI approach is protective of cancer endpoints. Water systems need to monitor the amount of the individual PFAS to effectively calculate the HI. The EPA intends to provide a web-based tool for ease of calculating the HI.

Economic Feasibility

The SDWA requires that EPA consider the incremental costs and benefits of the proposed MCLs. EPA’s Administrator may establish less stringent MCL if health benefits do not justify the costs of its implementation.

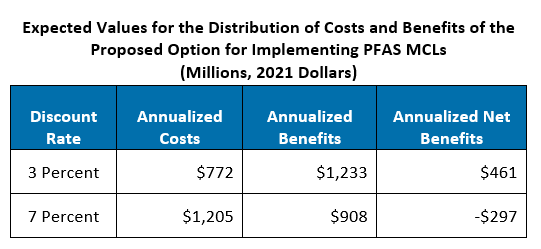

The EPA’s 663-page draft Economic Analysis for the Proposed Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances National Primary Drinking Water Regulation is available for public comment. Its findings may prove inconclusive, in part because the benefit-cost comparison is sensitive to the annual discount rate (as specified in OMB Circular A-94).

The estimated benefits of the Proposed Option exceed its estimated costs by $461 million annually using the 3% discount rate. However, applying the 7% discount rate yields negative net benefits amounting to $297 million annually. Notably, the EPA describes several health effects (e.g., immune, hepatic, endocrine, metabolic, reproductive, musculoskeletal) for which benefits are not quantifiable.

Nationwide compliance costs exceed $1 billion annually. Drinking water treatment costs comprise nearly 90 percent, as a large proportion of water providers that have sampled do not meet the proposed MCLs. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law committed $5 billion total for addressing PFAS contamination, leaving water providers to offset the balance through the courts and their insurance policies.

The assumptions and methodologies the EPA followed to quantify health benefits are likely to receive the greatest scrutiny—in large part from the significant scientific uncertainty of PFAS’ links to disease endpoints. The EPA quantified four health risk benefits including two non-cancer endpoints; cardiovascular disease (CVD) and low birth weight, and two cancer endpoints; and renal cell carcinoma and bladder cancer. Each category accounts for approximately half of the quantified benefits, although CVD risk reduction alone accounts for 43 percent.

Have questions about what this means for you? Confused about how to perform the HI calculation? Do you need technical and economic support for public comments? Please reach out below to hear from one of our experts.